|

You’re reading Ry’s Git Tutorial |

The Basics

Now that you have a basic understanding of version control systems in general, we can start experimenting with Git. Using Git as a VCS is a lot like working with a normal software project. You’re still writing code in files and storing those files in folders, only now you have access to a plethora of Git commands to manipulate those files.

For example, if you want to revert to a previous version of your project, all you have to do is run a simple Git command. This command will dive into Git’s internal database, figure out what your project looked like at the desired state, and update all the existing files in your project folder (also known as the working directory). From an external standpoint, it will look like your project magically went back in time.

This module explores the fundamental Git workflow: creating a repository, staging and committing snapshots, configuring options, and viewing the state of a repository. It also introduces the HTML website that serves as the running example for this entire tutorial. A very basic knowledge of HTML and CSS will give you a deeper understanding of the purpose underlying various Git commands but is not strictly required.

Create the Example Site

Before we can execute any Git commands, we need to create the example

project. Create a new folder called my-git-repo to store the

project, then add a file called index.html to it. Open

index.html in your favorite text editor and add the following

HTML.

<!DOCTYPE html><htmllang="en"><head><title>A Colorful Website</title><metacharset="utf-8"/></head><body><h1style="color: #07F">A Colorful Website</h1><p>This is a website about color!</p><h2style="color: #C00">News</h2><ul><li>Nothing going on (yet)</li></ul></body></html>

Save the file when you’re done. This serves as the foundation of our

example project. Feel free to open the index.html in a web browser

to see what kind of website it translates to. It’s not exactly pretty,

but it serves our purposes.

Initialize the Git Repository

Now, we’re ready to create our first Git repository. Open a command prompt (or Git Bash for Windows users) and navigate to the project directory by executing:

cd/path/to/my-git-repo

where /path/to/my-git-repo is a path to the folder created in

the previous step. For example, if you created my-git-repo on your

desktop, you would execute:

cd~/Desktop/my-git-repo

Next, run the following command to turn the directory into a Git repository.

gitinit

This initializes the repository, which enables the rest of Git’s

powerful features. Notice that there is now a .git directory in

my-git-repo that stores all the tracking data for our repository

(you may need to enable hidden files to view this folder). The

.git folder is the only difference between a Git repository and an

ordinary folder, so deleting it will turn your project back into an unversioned

collection of files.

View the Repository Status

Before we try to start creating revisions, it would be helpful to view the status of our new repository. Execute the following in your command prompt.

gitstatus

This should output something like:

#On branchmaster## Initial commit##Untracked files:# (use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)##index.htmlnothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

Ignoring the On branch master portion for the time being, this

status message tells us that we’re on our initial commit and that we have

nothing to commit but “untracked files.”

An untracked file is one that is not under version control.

Git doesn’t automatically track files because there are often project

files that we don’t want to keep under revision control. These include

binaries created by a C program, compiled Python modules (.pyc

files), and any other content that would unnecessarily bloat the repository. To

keep a project small and efficient, you should only track source files

and omit anything that can be generated from those files. This latter

content is part of the build process—not revision control.

Stage a Snapshot

So, we need to explicitly tell Git to add index.html to the

repository. The aptly named git add command tells Git to start

tracking index.html:

gitaddindex.htmlgitstatus

In place of the “Untracked files” list, you should see the following status.

#Changes to be committed:# (use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)##new file: index.html

We’ve just added index.html to the

snapshot for the next commit. A snapshot represents the state

of your project at a given point in time. In this case, we created a snapshot

with one file: index.html. If we ever told Git to revert to this

snapshot, it would replace the entire project folder with this one file,

containing the exact same HTML as it does right now.

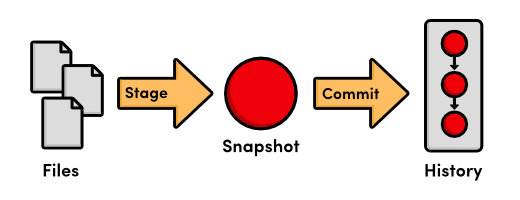

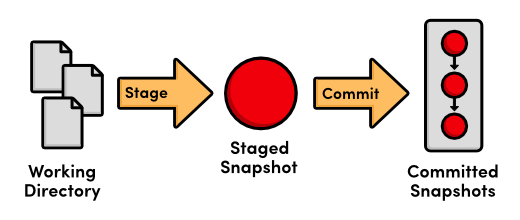

Git’s term for creating a snapshot is called staging because we can add or remove multiple files before actually committing it to the project history. Staging gives us the opportunity to group related changes into distinct snapshots—a practice that makes it possible to track the meaningful progression of a software project (instead of just arbitrary lines of code).

Commit the Snapshot

We have staged a snapshot, but we still need to commit it to the project history. The next command will open a text editor and prompt you to enter a message for the commit.

gitcommit

Type Create index page for the message, leave the remaining

text, save the file, and exit the editor. You should see the message 1

files changed among a mess of rather ambiguous output. This changed file

is our index.html.

As we just demonstrated, saving a version of your project is a two step process:

- Staging. Telling Git what files to include in the next commit.

- Committing. Recording the staged snapshot with a descriptive message.

Staging files with the git add command doesn’t actually

affect the repository in any significant way—it just lets us get our

files in order for the next commit. Only after executing git

commit will our snapshot be recorded in the repository. Committed

snapshots can be seen as “safe” versions of the project. Git will

never change them, which means you can do almost anything you want to your

project without losing those “safe” revisions. This is the

principal goal of any version control system.

View the Repository History

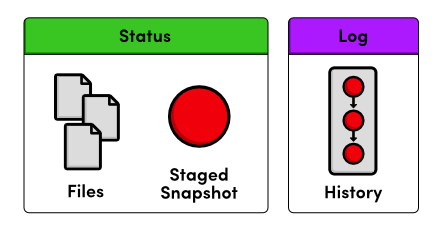

Note that git status now tells us that there is nothing

to commit, which means our current state matches what is stored in the

repository. The git status command will only show us

uncommitted changes—to view our project history, we need a new

command:

gitlog

When you execute this command, Git will output information about our one and only commit, which should look something like this:

commitb650e4bd831aba05fa62d6f6d064e7ca02b5ee1bAuthor:unknown <user@computer.(none)>Date:Wed Jan 11 00:45:10 2012 -0600Create index page

Let’s break this down. First, the commit is identified with a very

large, very random-looking string (b650e4b...). This is an SHA-1

checksum of the commit’s contents, which ensures that the commit will

never be corrupted without Git knowing about it. All of your SHA-1 checksums

will be different than those displayed in this tutorial due to the different

dates and authors in your commits. In the next module, we’ll see how a

checksum also serves as a unique ID for a commit.

Next, Git displays the author of the commit. But since we haven’t told

Git our name yet, it just displays unknown with a generated

username. Git also outputs the date, time, and timezone (-0600) of

when the commit took place. Finally, we see the commit message that was entered

in the previous step.

Configure Git

Before committing any more snapshots, we should probably tell Git who we

are. We can do this with the git config command:

gitconfig--globaluser.name"Your Name"gitconfig--globaluser.emailyour.email@example.com

Be sure to replace Your Name and

your.email@example.com with your actual name and email. The

--global flag tells Git to use this configuration as a default for

all of your repositories. Omitting it lets you specify different user

information for individual repositories, which will come in handy later on.

Create New HTML Files

Let’s continue developing our website a bit. Start by creating a file

called orange.html with the following content.

<!DOCTYPE html><htmllang="en"><head><title>The Orange Page</title><metacharset="utf-8"/></head><body><h1style="color: #F90">The Orange Page</h1><p>Orange is so great it has a<spanstyle="color: #F90">fruit</span>named after it.</p></body></html>

Then, add a blue.html page:

<!DOCTYPE html><htmllang="en"><head><title>The Blue Page</title><metacharset="utf-8"/></head><body><h1style="color: #00F">The Blue Page</h1><p>Blue is the color of the sky.</p></body></html>

Stage the New Files

Next, we can stage the files the same way we created the first snapshot.

gitaddorange.htmlblue.htmlgitstatus

Notice that we can pass more than one file to git add. After

adding the files, your status output should look like the following:

#On branchmaster#Changes to be committed:# (use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)##new file: blue.html#new file: orange.html

Try running git log. It only outputs the first commit, which

tells us that blue.html and orange.html have not yet

been added to the repository’s history. Remember, we can see

staged changes with git status, but not with git

log. The latter is used only for committed changes.

Commit the New Files

Let’s commit our staged snapshot:

gitcommit

Use Create blue and orange pages as the commit message, then

save and close the file. Now, git log should output two commits,

the second of which reflects our name/email configuration. This project history

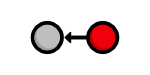

can be visualized as:

Each circle represents a commit, the red circle designates the commit we’re currently viewing, and the arrow points to the preceding commit. This last part may seem counterintuitive, but it reflects the underlying relationship between commits (that is, a new commit refers to its parent commit). You’ll see this type of diagram many, many times throughout this tutorial.

Modify the HTML Pages

The git add command we’ve been using to stage

new files can also be used to stage modified files. Add the

following to the bottom of index.html, right before the closing

</body> tag:

<h2>Navigation</h2><ul><listyle="color: #F90"><ahref="orange.html">The Orange Page</a></li><listyle="color: #00F"><ahref="blue.html">The Blue Page</a></li></ul>

Next, add a home page link to the bottom of orange.html and

blue.html (again, before the </body> line):

<p><ahref="index.html">Return to home page</a></p>

You can now navigate between pages when viewing them in a web browser.

Stage and Commit the Snapshot

Once again, we’ll stage the modifications, then commit the snapshot.

gitstatusgitaddindex.htmlorange.htmlblue.htmlgitstatusgitcommit-m"Add navigation links"

The -m option lets you specify a commit message on the command

line instead of opening a text editor. This is just a convenient shortcut (it

has the exact same effect as our previous commits).

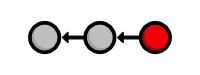

Our history can now be represented as the following. Note that the red circle, which represents the current commit, automatically moves forward every time we commit a new snapshot.

Explore the Repository’s History

The git log command comes with a lot of formatting options, a

few of which will be introduced throughout this tutorial. For now, we’ll

just use the convenient --oneline flag:

gitlog--oneline

Condensing output to a single line is a great way to get a high-level

overview of a repository. Another useful configuration is to pass a filename to

git log:

gitlog--onelineblue.html

This displays only the blue.html history. Notice that the

initial Create index page commit is missing, since

blue.html didn’t exist in that snapshot.

Conclusion

In this module, we introduced the fundamental Git workflow: edit files, stage a snapshot, and commit the snapshot. We also had some hands-on experience with the components involved in this process:

The distinction between the working directory, the staged snapshot, and committed snapshots is at the very core of Git version control. Nearly all other Git commands manipulate one of these components in some way, so understanding the interplay between them is a fantastic foundation for mastering Git.

The next module puts our existing project history to work by reverting to previous snapshots. This is all you need to start using Git as a simple versioning tool for your own projects.

Quick Reference

git init- Create a Git repository in the current folder.

git status- View the status of each file in a repository.

git add <file>- Stage a file for the next commit.

git commit- Commit the staged files with a descriptive message.

git log- View a repository’s commit history.

git config --global user.name "<name>"- Define the author name to be used in all repositories.

git config --global user.email <email>- Define the author email to be used in all repositories.