|

You’re reading Ry’s Git Tutorial |

Centralized Workflows

In the previous module, we shared information directly between two

developers’ repositories: my-git-repo and

marys-repo. This works for very small teams developing simple

programs, but larger projects call for a more structured environment. This

module introduces one such environment: the centralized

workflow.

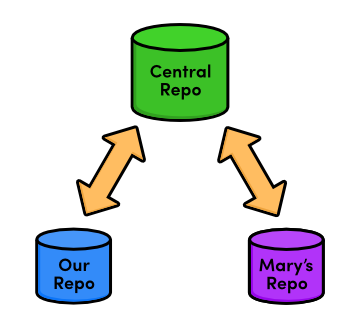

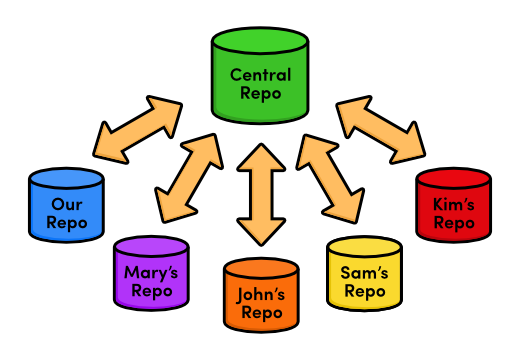

We’ll use a third Git repository to act as a central communication hub

between us and Mary. Instead of pulling changes into my-git-repo

from marys-repo and vice versa, we’ll push to and fetch from

a dedicated storage repository. After this module, our workflow will look like

the following.

Typically, you would store the central repository on a server to allow internet-based collaboration. Unfortunately, server configuration can vary among hosting providers, making it hard to write universal step-by-step instructions. So, we’ll continue exploring remote repositories using our local filesystem, just like in the previous module.

If you have access to a server, feel free to use it to host the central repository that we’re about to create. You’ll have to provide SSH paths to your server-based repository in place of the paths provided below, but other than that, you can follow this module’s instructions as you find them. For everyone else, our network-based Git experience will begin in the next module.

If you’ve been following along from the previous module, you already have everything you need. Otherwise, download the zipped Git repositories from the above link, uncompress them, and you’re good to go.

Create a Bare Repository (Central)

First, let’s create our central “communication hub.”

Again, make sure to change /path/to/my-git-repo to the actual path

to your repository. If you’ve decided to host the central repository on

your server, you should SSH into it and run the git init command

wherever you’d like to store the repository.

cd/path/to/my-git-repocd..gitinit--barecentral-repo.git

As in the very first module, git init creates a new repository.

But this time, we used the --bare flag to tell Git that we

don’t want a working directory. This will prevent us from developing in

the central repository, which eliminates the possibility of messing up another

user’s environment with git push. A central repository is

only supposed to act as a storage facility—not a development

environment.

If you examine the contents of the resulting central-repo.git

folder, you’ll notice that it contains the exact same files as the

.git folder in our my-git-repo project. Git has

literally gotten rid of our working directory. The conventional

.git extension in the directory name is a way to convey this

property.

Update Remotes (Mary and You)

We’ve successfully set up a central repository that can be used to

share updates between us, Mary, and any other developers. Next, we should add

it as a remote to both marys-repo and

my-git-repo.

cdmarys-repogitremotermorigingitremoteaddorigin../central-repo.git

Now for our repository:

cd../my-git-repogitremoteaddorigin../central-repo.gitgitremotermmary

Note that we deleted the remote connections between Mary and our

my-git-repo folder with git remote rm. For the rest

of this module, we’ll only use the central repository to share

updates.

If you decided to host the central repository on a server, you’ll need

to change the ../central-repo.git path to:

ssh://user@example.com/path/to/central-repo.git, substituting your

SSH username and server location for user@example.com and the

central repository’s location for

path/to/central-repo.git.

Push the Master Branch (You)

We didn’t clone the central repository—we just

initialized it as a bare repository. This means it doesn’t have any of

our project history yet. We can fix that using the git push

command introduced in the last module.

gitpushoriginmaster

Our central repository now contains our entire master branch,

which we can double-check with the following.

cd../central-repo.gitgitlog

This should output the familiar history listing of the master

branch.

Recall that git push creates local branches in the

destination repository. We said it was dangerous to push to a friend’s

repository, as they probably wouldn’t appreciate new branches appearing

at random. However, it’s safe to create local branches in

central-repo.git because it has no working directory, which means

it’s impossible to disturb anyone’s development.

Add News Update (You)

Let’s see our new centralized collaboration workflow in action by committing a few more snapshots.

cd../my-git-repogitcheckout-bnews-item

Create a file called news-3.html in my-git-repo

and add the following HTML.

<!DOCTYPE html><htmllang="en"><head><title>Middle East's Silent Beast</title><linkrel="stylesheet"href="style.css"/><metacharset="utf-8"/></head><body><h1style="color: #D90">Middle East's Silent Beast</h1><p>Late yesterday evening, the Middle East's largest design house—until now, silent on the West's colorful disagreement—announced the adoption of<spanstyle="color: #D90">Yellow</span>as this year's color of choice.</p><p><ahref="index.html">Return to home page</a></p></body></html>

Next, add a link to the “News” section of

index.html so that it looks like:

<h2style="color: #C00">News</h2><ul><li><ahref="news-1.html">Blue Is The New Hue</a></li><li><ahref="rainbow.html">Our New Rainbow</a></li><li><ahref="news-2.html">A Red Rebellion</a></li><li><ahref="news-3.html">Middle East's Silent Beast</a></li></ul>

Stage and commit a snapshot.

gitaddnews-3.htmlindex.htmlgitstatusgitcommit-m"Add 3rd news item"

Publish the News Item (You)

Previously, “publishing” meant merging with the local

master branch. But since we’re only interacting

with the central repository, our master branch is private again.

There’s no chance of Mary pulling content directly from our

repository.

Instead, everyone accesses updates through the public

master branch, so “publishing” means pushing to the

central repository.

gitcheckoutmastergitmergenews-itemgitbranch-dnews-itemgitpushoriginmaster

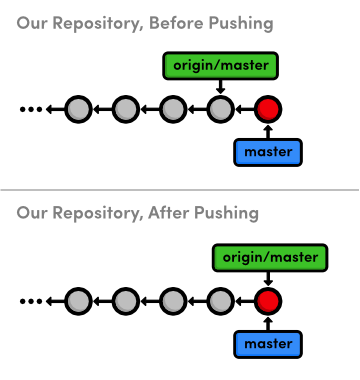

After merging into master as we normally would, git

push updates the central repository’s master branch

to reflect our local master. From our perspective, the push can be

visualized as the following:

master to the central repositoryNote that this accomplishes the exact same thing as going into the central

repository and doing a fetch/fast-forward merge, except git push

allows us to do everything from inside my-git-repo. We’ll

see some other convenient features of this command later in the module.

Update CSS Styles (Mary)

Next, let’s pretend to be Mary again and add some CSS formatting (she is our graphic designer, after all).

cd../marys-repogitcheckout-bcss-edits

Add the following to the end of style.css:

h1{font-size:32px;}h2{font-size:24px;}a:link,a:visited{color:#03C;}

And, stage and commit a snapshot.

gitcommit-a-m"Add CSS styles for headings and links"

Update Another CSS Style (Mary)

Oops, Mary forgot to add some formatting. Append the h3 styling

to style.css:

h3{font-size:18px;margin-left:20px;}

And of course, stage and commit the updates.

gitcommit-a-m"Add CSS styles for 3rd level headings"

Clean Up Before Publishing (Mary)

Before Mary considers pushing her updates to the central repository, she needs to make sure she has a clean history. This must be done by Mary, because it’s near-impossible to change history after it has been made public.

gitrebase-imaster

This highlights another benefit of using isolated branches to develop independent features. Mary doesn’t need to go back and figure out what changes need to be rebased, since they all reside in her current branch. Change the rebase configuration to:

pick681bd1cAdd CSS styles for headings and linkssquasheabac68Add CSS styles for 3rd level headings

When Git stops to ask for the combined commit message, just use the first commit’s message:

Add CSS styles for headings and links

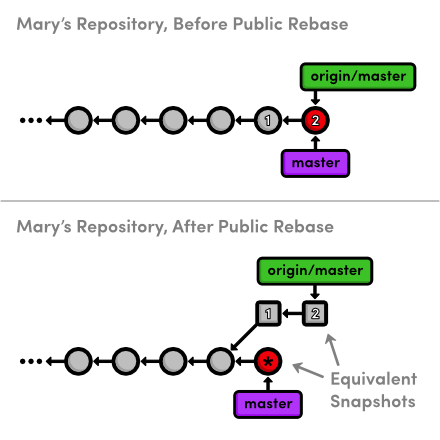

Consider what would have happened had Mary rebased after pushing to the central repository. She would be re-writing commits that other developers may have already pulled into their project. To Git, Mary’s re-written commits look like entirely new commits (since they have different ID’s). This situation is shown below.

The commits labeled 1 and 2 are the public commits that

Mary would be rebasing. Afterwards, the public history is still the exact same

as Mary’s original history, but now her local master branch

has diverged from origin/master—even though they represent

the same snapshot.

So, to publish her rebased master branch to the central

repository, Mary would have to merge with origin/master. This

cannot be a fast-forward merge, and the resulting merge commit is likely to

confuse her collaborators and disrupt their workflow.

This brings us to the most important rule to remember while rebasing: Never, ever rebase commits that have been pushed to a shared repository.

If you need to change a public commit, use the git revert

command that we discussed in Undoing

Changes. This creates a new commit with the required modifications instead

of re-writing old snapshots.

Publish CSS Changes (Mary)

Now that her history is cleaned up, Mary can publish the changes.

gitcheckoutmastergitmergecss-editsgitbranch-dcss-edits

She shouldn’t push the css-edits branch to the server,

since it’s no longer under development, and other collaborators

wouldn’t know what it contains. However, if we had all decided to

develop the CSS edits together and wanted an isolated environment to do so, it

would make sense to publish it as an independent branch.

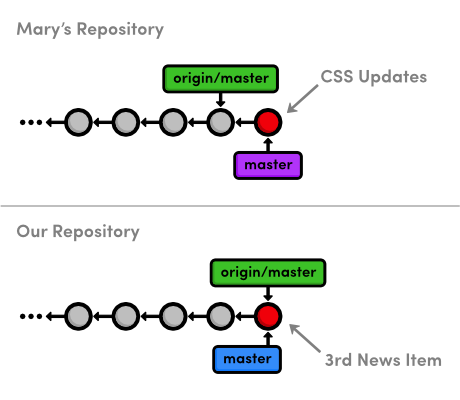

Mary still needs to push the changes to the central repository. But first, let’s take a look at the state of everyone’s project.

You might be wondering how Mary can push her local master up to

the central repository, since it has progressed since Mary last fetched from

it. This is a common situation when many developers are working on a project

simultaneously. Let’s see how Git handles it:

gitpushoriginmaster

This will output a verbose rejection message. It seems that Git won’t

let anyone push to a remote server if it doesn’t result in a fast-forward

merge. This prevents us from losing the Add 3rd news item commit

that would need to be overwritten for origin/master to match

mary/master.

Pull in Changes (Mary)

Mary can solve this problem by pulling in the central changes before trying

to push her CSS changes. First, she needs the most up-to-date version of the

origin/master branch.

gitfetchorigin

Remember that Mary can see what’s in origin/master and

not in the local master using the .. syntax:

gitlogmaster..origin/master

And she can also see what’s in her master that’s

not in origin/master:

gitlogorigin/master..master

Since both of these output a commit, we can tell that Mary’s history

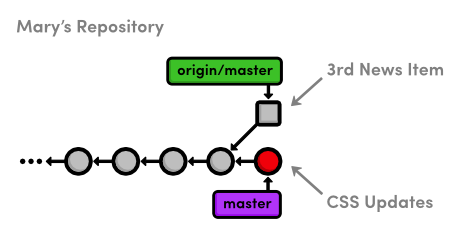

diverged. This should also be clear from the diagram below, which shows the

updated origin/master branch.

master branchMary is now in the familiar position of having to pull in changes from another branch. She can either merge, which cannot be fast-forwarded, or she can rebase for a linear history.

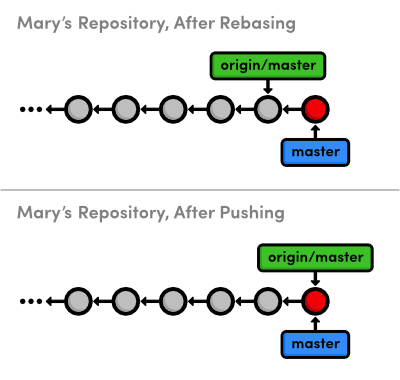

Typically, you’ll want to rebase your changes on top of those found in your central repository. This is the equivalent of saying, “I want to add my changes to what everyone else has already done.” As previously discussed, rebasing also eliminates superfluous merge commits. For these reasons, Mary will opt for a rebase.

gitrebaseorigin/mastergitpushoriginmaster

After the rebase, Mary’s master branch contains

everything from the central repository, so she can do a fast-forward push to

publish her changes.

masterPull in Changes (You)

Finally, we’ll switch back to our repository and pull in Mary’s CSS formatting.

cd../my-git-repogitfetchorigingitlogmaster..origin/master--statgitlogorigin/master..master--stat

Of course, the second log command won’t output anything, since we haven’t added any new commits while Mary was adding her CSS edits. It’s usually a good idea to check this before trying to merge in a remote branch. Otherwise, you might end up with some extra merge commits when you thought you were fast-forwarding your branch.

gitmergeorigin/master

Our repository is now synchronized with the central repository. Note that

Mary may have moved on and added some new content that we don’t know

about, but it doesn’t matter. The only changes we need to know about are

those in central-repo.git. While this doesn’t make a huge

difference when we’re working with just one other developer, imagine

having to keep track of a dozen different developers’ repositories in

real-time. This kind of chaos is precisely the problem a centralized

collaboration workflow is designed to solve:

The presence of a central communication hub condenses all this development into a single repository and ensures that no one overwrites another’s content, as we discovered while trying to push Mary’s CSS updates.

Conclusion

In this module, we introduced another remote repository to serve as the central storage facility for our project. We also discovered bare repositories, which are just like ordinary repositories—minus the working directory. Bare repositories provide a “safe” location to push branches to, as long as you remember not to rebase the commits that it already contains.

We hosted the central repository on our local filesystem, right next to both ours and Mary’s projects. However, most real-world central repositories reside on a remote server with internet access. This lets any developer fetch from or push to the repository over the internet, making Git a very powerful multi-user development platform. Having the central repository on a remote server is also an affordable, convenient way to back up a project.

Next up, we’ll configure a network-based repository using a service called GitHub. In addition to introducing network access for Git repositories, this will open the door for another collaboration standard: the integrator workflow.

Quick Reference

git init --bare <repository-name>- Create a Git repository, but omit the working directory.

git remote rm <remote-name>- Remove the specified remote from your bookmarked connections.